I couldn’t write in Belgrade. I was given a one-month writing residency in a cute little apartment along with a monthly stipend and I wrote nothing. I had applied for Sarajevo, but couldn’t get it as a Bosnian. They told me I had to go to a foreign country, and offered Serbia, which was about as foreign to me as my own bedroom. I did my MA course in Belgrade and lived there for ten months. My parents are Serbian, so are my siblings. My sister has lived in Belgrade for ten years and even her accent has changed over the years. This year I finally got Serbian citizenship, so the whole foreign country thing became even more ridiculous. Still, at the time I applied, I was technically a foreigner in Belgrade. So I got Belgrade. The ‘white city’ with sick lungs. I had to give up on my beloved Sarajevo, at least for the time being.

What was I doing at a writer’s residency? I couldn’t write and I couldn’t sleep. My insomnia was back big time. When I did sleep, I had either excruciating nightmares or sleep paralysis. I dreamed of bears chasing me through the woods, of buildings crashing down on me, of drowning. My eyes would wake up before my body and I would hallucinate a dark figure in the room, walking towards me. I would wake up screaming.

I have suffered from sleep-related problems my whole life. When I was little, I sometimes sleepwalked and would wake up in the middle of the night on the floor, fully dressed for school. Even in my sleep I was anxious to leave. But in those last years in Barcelona, when I received the invitation to the residency in Belgrade, my sleep patterns had improved significantly and I no longer saw the dark man in my room. It puzzled me why he was suddenly back now, in this little apartment in Belgrade. Somehow the city had triggered my sleep problems again and I was scared to go to bed, worried that night terrors would return.

Around five-six a.m. I would give up sleeping altogether and get out of the apartment.

The city was still asleep at that time. It seemed empty, abandoned, like after an apocalypse. I liked it best without people, when its tired brutalist beauty would reveal itself fully. The scars were there, too. All the bombs, all the myths. It’s like the city was telling me: Look how much madness I’ve been through and I still stand. There were moments when I felt we were equals, because we had both suffered under other people’s delusions. Other times I just saw the city as a language I would never learn, as if those streets and trams and buses and sidewalks were an unnecessarily difficult grammar.

Still, I liked to walk and read the graffiti. Sometimes they told stories of broken hearts and lost hopes. Other times they venerated war criminals. It was as if the face of the city echoed its citizens’ thoughts and dreams and fears. Their best and their worst. The marks said: There is a great sorrow here. They also said: But people are still people. They will love and hate and want and not have. They will write on the walls. One graffiti read I cry in the rain so my tears wouldn’t show. Another one read: Ratko Mladić - our hero. Another one read: We were happy, regardless. Another one read: Kosovo is Serbia. Another one read: Do you ever think of me when you read this? Another one read: A new Balkan federation of socialist republics! Another one read: No woman no cry. There was a portrait of Bob Dylan. There was a portrait of Radovan Karadžić. And so on.

Belgrade’s difficult sorrow found its way into me. I read a famous poem about it where the writer compared it to a swan. I kept looking for the beautiful wings described in those verses, but all I saw was an old and tired bird chasing its cygnets away. I would get on the wrong bus. I would spend too much money on food. I would walk around parked cars, everywhere, mourning Belgrade’s stolen sidewalks. I would cough - in the supermarkets, in the restaurants, in the parks, in the libraries. I would cough and cough and cough, and Belgrade would laugh at my unprepared Mediterranean lungs. Smoke was everywhere I went: cars made it, people made it, buildings made it, all of them eager to vent it out, push it into the streets. Sometimes I thought they needed all the smoke to hide the scars. But mostly I coughed and the smoke got in together with the sorrow.

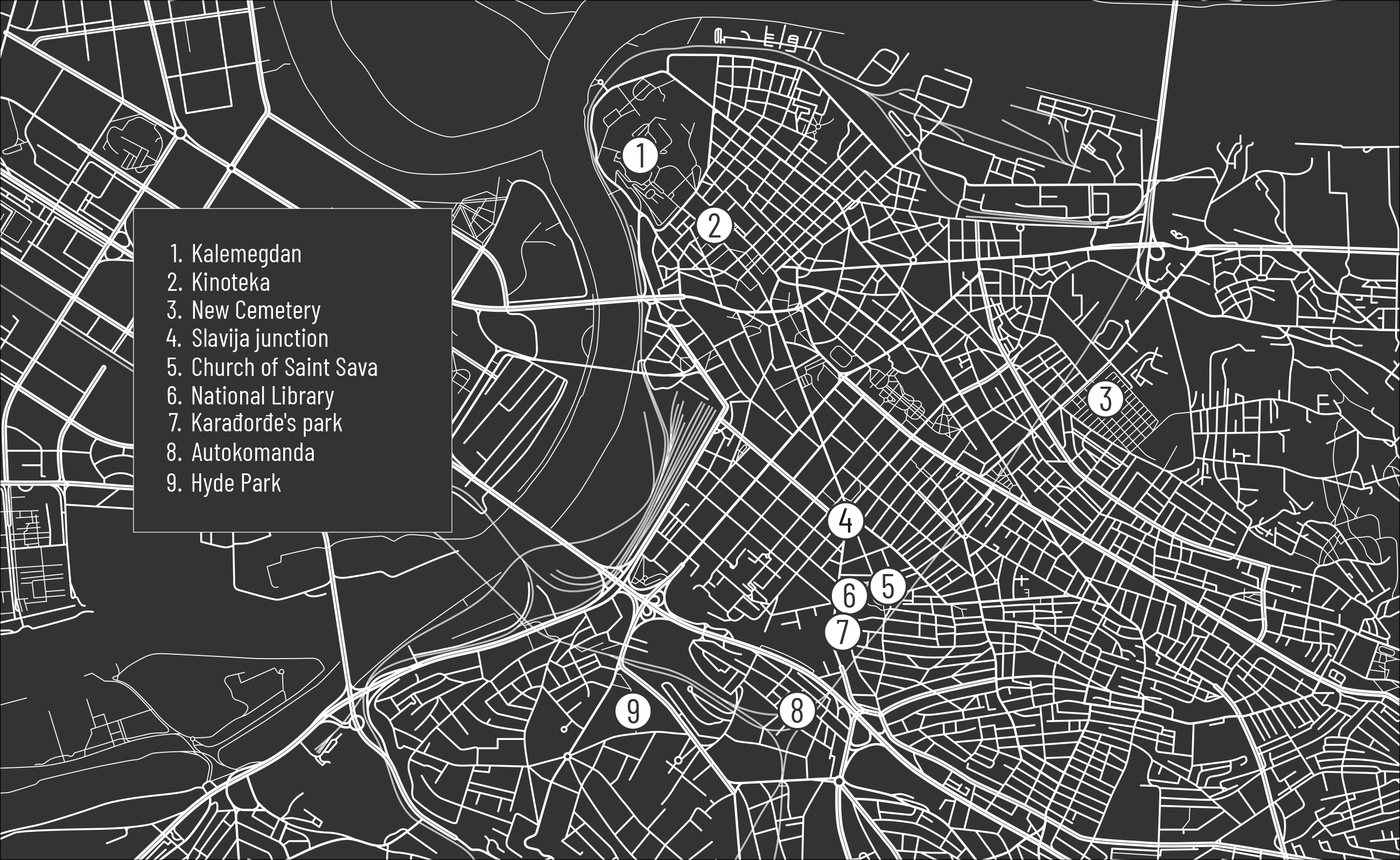

On those quiet mornings I would walk all the way through the Kalemegdan and to the place where the rivers meet. The Sava rushed towards the Danube, with all the painful stories she had collected over the decades - stories from my own country, told by smaller rivers: Drina and Una and Bosna and Vrbas. Stories too dark to be repeated. The Sava river swallowed them all up and pushed them restlessly towards the great Danube, the only one that could take it because it has already seen it all. It made me think of how they’re becoming one thing while remaining separate at the same time, their water molecules mixing up and pushing forwards, losing all identity before they reach the faraway Black Sea. It made me think of the words we put on land and water, and how land becomes heavy with them, closed off by borders and soaked with blood, whereas water bears witness and moves on - it flows away and becomes something else entirely.

I told a friend from Belgrade: I don’t know how you do it. I could never make it here. It’s too depressing. And she said that Belgrade is one of those cities that reveal what’s inside of us. It will chew you up and spit you out. But you will be you in the end, whether you like it or not. This made me think that perhaps the sorrow I encountered there wasn’t Belgrade’s, but my own. Perhaps this city was a huge filthy mirror. But then, maybe all cities are. Yet somehow, Belgrade amplifies everything: the good and the bad. It is like those places on the planet where gravity is slightly stronger. It makes you feel a bit heavier, even if you’re not completely aware of it. Perhaps that’s what Belgrade does, too: it will make you feel your weight. It will make you feel every wound, big or small, new or forgotten, and call you out on your hypocrisy for trying to hide them. It will find you alone, at the meeting of the rivers, early in the morning and say: Hello, asshole, I’ve been waiting for you. And you will recognise each other, silently and embarrassingly, like two addicts at an anonymous meeting. Did you think you were better than me?

I couldn’t be in the apartment for too long because it only reminded me of the fact that I wasn’t writing. I would cook something quick, answer my emails, check in with my friends abroad, and then go back to walking. I liked to go to the National Library to read or pretend to read, surrounded by anxious university students and their heavy textbooks. I liked the silence of young people learning. I liked how we were partaking of this silence together and how at the same time, inside our heads, different worlds were being unfurled. One of those students, I thought, is going to be a doctor and what he or she is learning today, right now, this very minute, might save someone else’s life. One of them is going to be a lawyer and what he or she is learning today, right now, this very minute, will help a guilty man get acquitted. One of them will have no use for what he or she is learning today and will perhaps go on to become a writer. Many will be average. Many will think they’re not. Some will fail. Some will move away to Germany. Some will develop cancer or diabetes or simply die in their sleep. Every time I left the library building, it felt like I had entered a pocket of time different from the rest of the world. Sometimes it felt like only a few minutes had passed on the outside while I had read for hours, surrounded by those students.

Tourists gathered by the Library to take photos of the Church of Saint Sava, an Orthodox temple remotely resembling the Hagia Sophia. The temple looms large over the Library and people cross themselves when they walk past it or drive by. And so, while some were silently learning facts in the smaller building, others were praying to a higher deity in the church. I thought how sad it was that nobody blessed themselves when they walked past the library and how a single book could become more important and earn a bigger temple than a hundred thousand others. In that quiet dichotomy of the Karađorđe’s park, I thought how all writers are somehow competing against that one book, a single myth, constantly losing to it, failing, and starting again. And there I was - at a writing residency - not even trying.

Some evenings I would visit the Yugoslav film archive - Kinoteka. I spent my last year in Barcelona in a shared apartment in the dangerous district of Raval, with drug dealers and prostitutes for neighbours and hard-working migrant families struggling to make it through another month. What made it worth it was the Filmoteca de Catalunya, just three minutes away from my flat, where I could run away from my four obnoxious roommates and spend three to four hours hooked to the silver screen. I found the same comfort at the Belgrade Kinoteka, watching whatever was on show, old or new, good or bad, sharing a conspiratorial smile with fellow loners in the theatre. Just like the library, the cinema made me feel at home, only this time we were all partaking of the same experience, no matter how differently we might have translated it inside ourselves. Moving images have always soothed my word-ridden mind, getting me away from the written language and into a visual one, while at the same time motivating me to go on writing. No book has made me want to write as much as some films have. And in this respectful interaction of two very different arts I have found the little truths to chase after in my own writing.

The general lack of greenery in the city centre depressed both me and my lungs, so I roamed the streets looking for parks and other green havens. Pretty soon, Hyde Park became my favourite, even though there are bigger and more beautiful forests in Belgrade. I liked the triangularity of it and how I could suddenly be in the woods, oblivious to the traffic surrounding the park, as if I had gone far away. I liked the yellow lights that would appear in the late afternoon, quietly and unobtrusively covering the park in golden hues. The earth smelled of dust and leaves after the rain and minute life would crawl out of ferns and under rocks to dry out in the soothing sun. One time I saw a poster of a missing dog, a cute little Jack Russel terrier with big brown eyes, and I was certain I would find him in the hidden corners of Hyde Park. I wanted to be the one to bring him back to his family, to do something good, as if to atone for the fact that I wasn’t writing. I called and called, though I can’t even remember which name now. After a while I gave up looking and some days later, walking by the poster again, I realized that the owner had put it up more than a year ago. I had been calling a ghost. My mission of performing a good and selfless deed was lost as well.

My stubborn legs walked me all over Voždovac, Vračar, Zvezdara, Dorćol, and other parts of the city. More often than not, they would take me to the New Cemetery, built one hundred years before I was born, and I would walk cheerfully through its main arch and into the valley of the dead. The military graves were of no interest to me, I have always preferred writers to generals. I would walk to the grave of the poet Branko Miljković, whose sky spread between the fingers I had once stolen, and think of those lonely days of my postgraduate year when I used to bring him a red rose every two weeks. This time I was older, more realistic, and perhaps more bitter, too. This time I went straight to Danilo Kiš. I would sit by his side and tell him I wasn’t writing. I told him there was too much sorrow and emptiness and how this city inflated it inside my head. I told him I was not a dedicated genius like him, but a simple mortal woman with insomnia and bad thyroid. Danilo said nothing, because he was dead. It was always more difficult to leave the cemetery than to enter it, and this made me think of what the Sybil had told Aeneas once.

But there was no need to go to a cemetery to feel close to Death in Belgrade. Somehow I felt its presence everywhere: it was crumbling the buildings, freezing the homeless, sucking out oxygen, strangling love. It was in the couple fighting in the supermarket, exchanging fuck you’s like hello’s. It was in the little boy I once saw from the window - his father was yelling at him, telling him how stupid he was, a complete retard, while the boy just stared at his white sneakers. It was in the tired and edgy drivers, shouting at each other at the impossible Slavija junction. It was in the wet corpses of old trees. Perhaps that was what Belgrade had to offer - it could show you the extreme, the excess, the fragile border between sanity and madness, between living and surviving. In its lack of clean air it somehow made you more eager to breathe. And maybe it was this omnipresence of Death that made me feel more eager to keep walking, keep breathing, keep reading or watching films in order to find my thin thread through the labyrinth.

During my last few days in Belgrade, I stumbled upon a novel by Georgi Gospodinov, called The Physics of Sorrow, translated into Serbian and published by Geopoetika. I became completely fascinated with the writing and the story, rereading the book the minute I had finished it. The myth of the Minotaur rethought and retold as the story of an abandoned child lost and helpless inside a massive labyrinth would go on to inspire my next short story collection. I copied one sentence from Gospodinov’s novel into a big grey notebook, went to Sarajevo and finally, after a long time, started writing.

Still, the sorrow that shaped the book (Milk Teeth came out in 2020) wasn’t Sarajevo’s sorrow. It wasn’t even Gospodinov’s sorrow. It was Belgrade’s. Less than a year after my residency had ended, I moved there. A friend drove me and my stuff all the way from sunny Barcelona to the scorched cement-lungs of Autokomanda. I unpacked my bags, stacked my books on new shelves, bought a public transport pass, applied for citizenship and an ID, and so, pretty soon, became a Belgradian. (My north-Bosnian accent has proudly lingered on.)

It was different this time. I made friends. I went running. I developed my own Belgrade rituals. The sorrow was still there, but somehow domesticated. After a couple of months, I walked again to the place where the rivers meet. The city was just waking up. It seemed like it was saying: You again? So I smiled and thought: I’m tougher now, show me what you’ve got.

And it did.

White City

1

at night

you break off like a scab

and I am thin again and I sting

I have nothing to say to you

nothing new and nothing good

the poem about you is a stone in the silence of my kidney

I don’t write poems and I don’t recognise you

I know only that you are almost like a lie

or a truth unspoken

about your whiteness

whiteness is a word that has remained

devouring all other words

saying nothing, chewing, toothless whiteness

2

at night

I scratch where it’s white

dragging myself out of your dark vein

and spilling over the asphalt

here the lights are muted

and there’s a scent of grills in the mist

night turns your heavy corpse over the fire

there’s no fire here and I keep coughing

I cough you up

I crumble your fragile monstrosity

what can I say about you?

you’re indifferent

big cities are always indifferent

3

and there’s whiteness in me too

but that’s nothing to do with you

you only fatten it

you cough me up

tell me have you ever seen

between two roundabouts

at least one clean sentence?

something concrete, like a tram

maybe I don’t know how to look

mutedly, everything thunders, but muted

in the silence of the blood

isolated within you like a bacterium

I don’t want to die here

4

maybe even the beggars are silent tonight

they cross to the other side of the road

in the kiosk the cigarettes are silent, as are

the chocolate bananas

and the children’s bible

your lights are silent

one should move in you

maybe that’s the way

to reach the river, one or the other,

pretend it’s sea

pretend it matters which

but you’re not to blame

you didn’t name the water

or yourself, or me

5

at night

I count up the dead in my pockets

I move mutedly, morosely

muddily

rain slows your circulation

a drunken man says

the trams aren’t running, miss,

nothing

is running

his face is moist

and that nothing of his is as big as the city

it swallows ravens and trolleybuses

I am silent, silent

and I gather up the marsh

6

while you lie calm

like a paraplegic bear

defeated

your tracks wail a ‘please’

you spare your children

theirs is a white nostalgia

you need an outsider for your dirty work

at night we don’t recognise each other

something has stopped within us

and it’s hard to love us

I heard you

I pull on double gloves

and drag the bear to the river

7

is this November

or has fear frozen your streets?

the greatest is the emptiness of a children’s playground

in vain I seek a metaphor for sky

but the sky is nothing

just a pain in the neck’s vertebrae

when I remove my glasses, you are the hobby

of a lazy watercolourist

and a woman is dragging two children down the asphalt

no, they’re not children

they’re bags full of rubbish

and on your damp oak skin the scab is not a lost cat

but rediscovered death

8

is this November

or have I just chilled in the emptiness

of your stomach?

I need frontiers

but you spread like village gossip

you disappear more swiftly than me, in the smog

your god has given up

your traffic lights are bleeding

they reveal my whiteness

the white nostrils of my generation

the whiteness between letters and ribs

is this November

or have we just recognised each other?

9

whiteness in the morning is a target

and the clock ticks frenziedly

the white second that is coming

isn’t sorrow but a gap

the longest key on the board

the reason why postmen are late

why we don’t touch

your skin is hidden under posters

a thousand plasters over gangrene

where your children learn their letters

к о с о в о ј е с р б и ј а

children hungry for stale whiteness

look for each other in the fragile façades

10

today November is dying

and we have reached the river

a woman, white inside, polished,

and a bear, unwhite, on her back

so this is what you wanted – that I kill you

while your children are asleep?

this is no Greek tragedy

I have no hands, nor words for that

listen, those are cats beneath the bridges

you are already waking, angry, disappointed

in the morning, beside the river, we are a simple truth:

if I throw you off

who will throw me?

Poem translated by Celia Hawkesworth.

Lana Bastašić, born in Zagreb in 1986, has published three collections of short stories – Trajni pigmenti (2010), Vatrometi (2013) and Mliječni zubi (2020) –, one book of children’s stories, and one of poetry. She is the co-founder of 3+3 sisters, a project that aims to promote female writers from the Balkans. Her debut novel Catch the Rabbit (2018), published in English translation in 2021, was shortlisted for the 2019 NIN award, Serbia’s most prestigious literary accolade, and was awarded the 2020 European Union Prize for Literature and 2021 Latisana per il Nord-est Prize. The novel has been translated into 18 languages. Bastašić lives in Belgrade.

Photo credits: © Lana Bastašić

Photo of Lana Bastašić: © Radmila Vankoska

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri